Steven Pinker Interview: Inside the Mind of One of the World's Most Influential Thinkers

Written by Marc Parker and Melissa Benefield Parker, Posted in Interviews Authors

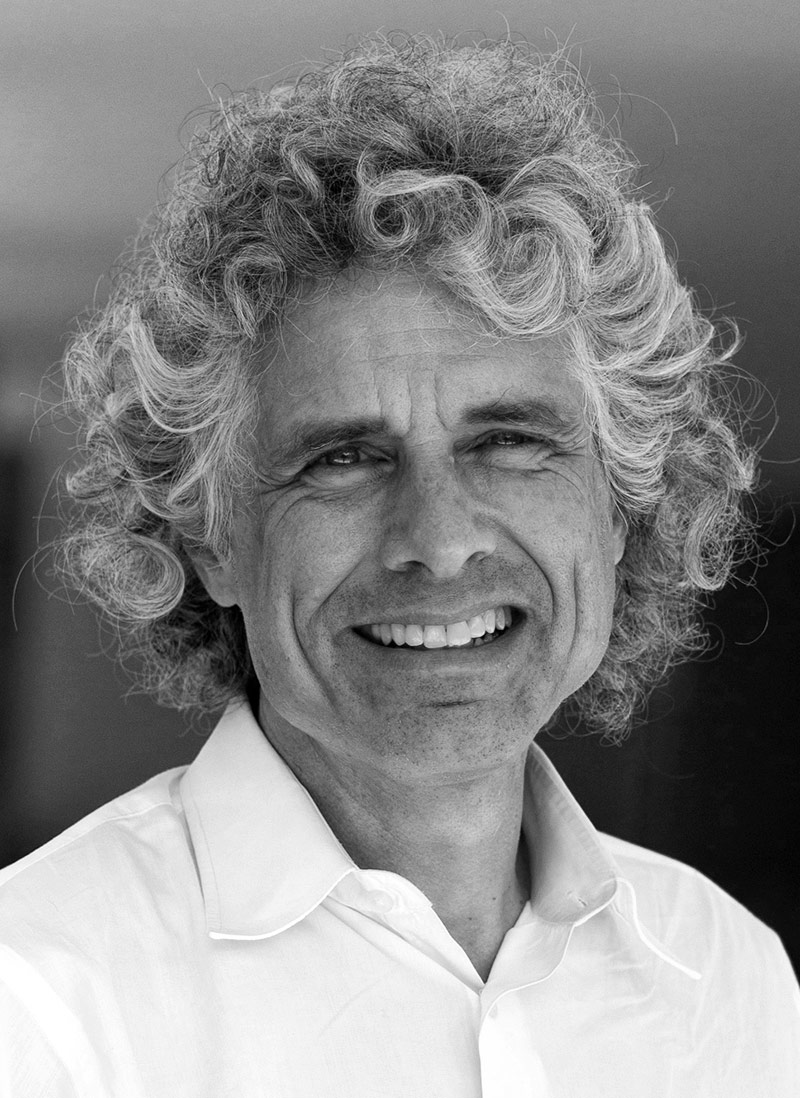

Image attributed to Rebecca Goldstein

Steven Pinker is an experimental psychologist and one of the world’s foremost writers on language, mind and human nature. Currently Johnstone Family Professor of Psychology at Harvard University, Pinker has also taught at Stanford and MIT. His research on vision, language and social relations has won prizes from the National Academy of Sciences, the Royal Institution of Great Britain, the Cognitive Neuroscience Society and the American Psychological Association.

Pinker has received eight honorary doctorates, several teaching awards at MIT and Harvard and numerous prizes for his books The Language Instinct, How the Mind Works, The Blank Slate and The Better Angels of Our Nature. He is chair of the Usage Panel of the American Heritage Dictionary and often writes for The New York Times, Time and other publications. He has been named Humanist of the Year, Prospect magazine’s “The World’s Top 100 Public Intellectuals,” Foreign Policy’s “100 Global Thinkers,” and Time’s “The Top Most Influential People in the world Today.

"And we know from evolutionary biology that all living things will make sacrifices of themselves if they benefit enough of their relatives who carry the same genes. In some cases, such as the various high school and movie theater gunmen and in many suicide terrorists, these are people who have suffered from depression, often mental illness. They are selected out by the leaders of terrorist organizations, or they come to the realization by themselves that they can kind of redeem a wretched, pathetic life as a nobody with at least momentary fame and glory. So someone who’s a nobody can enjoy the fantasy of becoming a national celebrity even if they don’t live to enjoy it."

Released September 22, 2015, The Sense of Style: The Thinking Person’s Guide to Writing in the 21st Century, is Pinker’s latest book. He has been married to novelist and philosopher Rebecca Goldstein since 2007 and has two stepdaughters.

Melissa Parker (Smashing Interviews Magazine): Steve, The Sense of Style is quite an interesting read. How can “style” make the world a better place?

Steven Pinker: Three ways. It can enhance clear communication and prevent all of the frustration, error and waste that comes from having to decipher opaque prose. Second, it enhances trust. If a person has taken care in the composition of their writing, it gives reason to think that they have taken care in other details that you can’t see as easily.

That’s one of the reasons that dating sites like Match.com and OKCupid find that bad grammar in profiles is a strong turnoff, at least for women choosing men. Third, it adds to the beauty of the world. To a literate reader, a crisp sentence, an original figure of speech and a well-turned phrase are among life’s greatest pleasures.

Melissa Parker (Smashing Interviews Magazine): Most writers either adhere to the Associated Press (AP) Stylebook or the Chicago Manual of Style in writing. Should one or the other still be used as a guide?

Steven Pinker: Those are specialized style in a different sense from the one that I write about in The Sense of Style. Those tell you whether you should use a period in abbreviations and how to use a dash or a hyphen, and my book is not on that aspect of style in the sense of a style sheet. It’s about style in the sense of clear and graceful writing.

I do touch on some points like the the so-called serial comma or Oxford comma, but in general, it’s not about the mechanics of how to abbreviate words or where to put the hyphen, but rather how not to baffle your readers.

Melissa Parker (Smashing Interviews Magazine): A New Yorker article last year entitled, “Steven Pinker’s Bad Grammar,” by Nathan Heller, stated that you “fight pedantry with more pedantry” and that it was "difficult to shake the suspicion that your list of screwball rules simply seeks to justify bad habits that certain people would rather not be bothered to unlearn.” How do you answer those accusations?

Steven Pinker: The writer, Nathan Heller, literally does not know what he’s talking about. He’s an utter ignoramus, and he was raked by a slew of linguists and language commentators in subsequent commentaries who were just incredulous that The New Yorker could publish such an error-filled piece. There are a number of language writers who are just howling with disbelief at the errors that he made in that review. This is just a little bit of idiocy on The New Yorker’s part, and it's part of a pattern.

They freak out when anyone with a background from linguistics or science writes about language because they wanted language to be owned by literary intellectuals and cultural critics, and that’s really what’s going on there. The idea that grubby scientists and nerdy academics should talk about how language is used leads to kind of a turf battle because they say, “Hey, that’s our territory.”

Melissa Parker (Smashing Interviews Magazine): I’ll be willing to bet that Rebecca Goldstein is one of your favorite writers.

Steven Pinker: Absolutely. I liked her prose so much that I married the author. Yes.

Melissa Parker (Smashing Interviews Magazine): Rebecca said that you have changed the way she thinks. How does she influence you?

Steven Pinker: Each of us influence the other. As well as being a gifted novelist, she is a sharp-minded philosopher, and so she has improved the clarity and depth of my thinking about philosophical issues such as the nature of morality and objectivity and truth. I’ve also seen close-up how the mind of a creative writer works, since all of my writing is non-fiction in the sciences whereas she is a literary novelist.

From me, I think she has learned a great deal about the science of human beings, since that’s what I do. Her interest in science has been concentrated in physics and mathematics rather than the social and cognitive sciences, so she has learned about those from me.

Melissa Parker (Smashing Interviews Magazine): Were there childhood influences that helped to form your career paths?

Steven Pinker: I think a lot of what makes us what we are we don’t have any conscious access to. I think our genes make a huge difference. I think by “sheer chance” makes a huge difference, and that’s why you often see people coming out of the most unlikely backgrounds, a rural town in South Dakota or a village in India, who then go on to scientific and literary greatness. But, I think, as long as you have access some way or another to ideas and writing, which I did, then you can be influenced in that direction.

I certainly grew up in a family where ideas were discussed around the dinner table. My parents both had college degrees, and my mother, in particular, was and is a voracious reader. She is interested in everything, and to this day continues to send me interesting articles that I’ve missed and that often make their way into my writing.

I also show my mother drafts of what I’ve written to get her comments and advice. I think growing up in a Jewish community where there’s a long tradition of argumentation and debate, sharpened my critical faculties and whetted my appetite for intellectual exploration.

Melissa Parker (Smashing Interviews Magazine): Your parents realized you were intellectually gifted at an early age?

Steven Pinker: They certainly encouraged me. They didn’t send me to nerd camps or to highly specialized private schools. I went to public schools. They encouraged a well-rounded childhood, but they also bought me books and encouraged academic diligence, so they certainly helped. But they were not “stage parents” who gave up their lives to foster my career.

Melissa Parker (Smashing Interviews Magazine): Do you have a love/hate relationship with linguist and cognitive scientist Noam Chomsky?

Steven Pinker: I would put it differently because I try to keep strong emotions out of it. Rather, I would say, that there are some things he says that I agree with and others that I disagree with. I don’t subscribe to his politics. I’m not a radical leftist. I’m not an anarchist. I don’t have a romantic view of human nature. I don’t agree with his particular theories of grammar, which I think are too complicated and esoteric.

But I do recognize his brilliance and his enormous influence on the understanding of language and cognitive science, in particular his emphasis on the infinite combinatorial creative power of language, how it allows us to express an unlimited number of thoughts with a finite set of rules on the fact that the mind is pre-programmed to learn language and that you can’t really understand how children succeed without knowing that they are built to interpret speech in terms of grammatical rules. I also acknowledge that he’s made a number of stupendously important discoveries about how language works, in particular, the phenomenon of the linguist’s COMP movement, which even his detractors and enemies incorporate in some way into their theories.

Melissa Parker (Smashing Interviews Magazine): Some people take the views of religious leaders and political pundits as their own. Is it laziness that stops them from thinking for themselves and forming their own opinions?

Steven Pinker: Well, it’s not entirely laziness because all of us rely on the expertise of others. I go into a dentist’s office, open my mouth and let her drill my teeth. I don’t really understand the principle behind dentistry, but I trust that she knows what she’s doing. Likewise, when my accountant fills out my tax forms. It’s in the nature of human beings to distribute intellectual labor that different people have different expertise, and we’re successful as a species because we divide up the lot.

But of course, that creates an opening for would-be experts in moral and spiritual values, and if they do a convincing enough job, then people believe what they say for the same reason that I believe that my dentist knows what she’s doing. It’s not just the leaders, but we also take cues from our neighbors. We assume that there’s some kind of wisdom of the crowd or safety in numbers. So when enough people around us believe, we tend to believe, and often we’re right. If people don’t eat a particular mushroom because they think it’s poisonous, it would be good to avoid it because it may be poisonous.

The problem is since we’ve invented science, we have discovered that a lot of beliefs that are conventional wisdom or the creeds from some charismatic leader are utterly false. We know now that if you really want to know how the world works, you have to be skeptical of dogma, skeptical of charisma, skeptical of revered ancient texts, and that the vast majority of our beliefs are false unless they are validated scientifically.

Melissa Parker (Smashing Interviews Magazine): Why do some people seek out martyrdom and are willing to die for their religious beliefs?

Steven Pinker: Some of them sincerely believe in the doctrine of the afterlife, so they think they will be rewarded in paradise whether by 72 virgins or by a nice harp and halo in the clouds, depending on your theology, so they actually don’t think they are making a sacrifice. They’re deluded, but that’s their belief.

Sometimes the studies of conditions that lead to martyrdom like Japanese kamikaze pilots show that they don’t have a whole lot of choice. They are often brutalized and intimidated, and their life is a living hell, so they aren’t losing a whole lot. In other cases, such as Palestinian terrorists, their families are amicably rewarded both in prestige and in cash, so a person who is kind of a loser and a nobody can benefit his family by blowing himself up.

And we know from evolutionary biology that all living things will make sacrifices of themselves if they benefit enough of their relatives who carry the same genes. In some cases, such as the various high school and movie theater gunmen and in many suicide terrorists, these are people who have suffered from depression, often mental illness. They are selected out by the leaders of terrorist organizations, or they come to the realization by themselves that they can kind of redeem a wretched, pathetic life as a nobody with at least momentary fame and glory. So someone who’s a nobody can enjoy the fantasy of becoming a national celebrity even if they don’t live to enjoy it.

Melissa Parker (Smashing Interviews Magazine): What would you say has been the most amazing scientific discovery of 2015?

Steven Pinker: Let’s see. We’re in October. Can’t say. It would take me too long to think about what has happened between January 1 and now, across so many different fields from physics to psychology to genetics. So, yeah, I can’t answer that.

Melissa Parker (Smashing Interviews Magazine): Researchers recently found a pregnant 48-million-year old horse with a preserved placenta in Germany.

Steven Pinker: That is amazing. So many fields of science are advancing so rapidly. My own memory would not be able to single out whether it happened in January of this year or December of last year. Certainly the recovery of ancient DNA is a stupendous accomplishment as is the study of the aggregate effect of thousands of genes on psychological traits.

It used to be thought that everyone was looking for a gene for musical talent or the gene for intelligence. Now we know that was looking for the wrong thing, that there are thousands of genes that affect any trait. Certainly the results coming out of the Large Hadron Collider in Switzerland are amazing, as is the discovery of more and more human fossils in South Africa. We could go on.

Melissa Parker (Smashing Interviews Magazine): Do you ever “play” in life, or is your work your “play”?

Steven Pinker: That’s a lot of it, but Rebecca and I do play hard as well as work hard, especially during the summer. We are avid cyclists and kayakers. We like hiking. We both enjoy reading. We take long walks in the city of Boston. We spend summers on Cape Cod. I think both of us work very intensely, but we also enjoy the other things in life.

Melissa Parker (Smashing Interviews Magazine): What’s next, Steve?

Steven Pinker: What’s next is a reissue of my 2002 book, The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature. I’m writing an Afterword about what the reaction to the book has been and what has developed in the last dozen years since the book came out. Penguin Books will be reissuing it with this new Afterword sometime next year.

I know from experience that a key talent you have to develop in interviews is to know when to stop talking (laughs). After you finish your answer, resist the temptation to keep rambling on and shut up, so that’s what I’m trying to do.

© 2015 Smashing Interviews Magazine. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without the express written consent of the publisher.